Visualizing a Regional Community

The accompanying map locates ethnic Mexican communities in the neighborhoods, towns, and cities where they resided in the first half of the twentieth century. By placing these communities on a map we get a representative, yet incomplete glance of the diversity of the ethnic Mexican experience in the region. In its current state, visitors can see the variety of Mexican residences in the Midwest with the plotting of metropolitan areas like Greater Kansas City, St. Louis, and Omaha, as well as small cities like Wichita and Topeka, and rural strongholds in Scottsbluff County, Nebraska, and a number of small towns throughout Kansas. Viewers will note multiple neighborhoods of Mexican inhabitance within cities and larger metropolitan areas. One can also see the multiplicity of rural residence and clustering within certain subsections of a state or region. After reviewing such an array of residences, we are left to ask, why here? Or why not there? Employment and labor networks partially answer these questions, but what continued to attract migrants? Or better yet, what maintained and motivated their daily lives throughout the Lower Midwest.

Of course, labor is still part of this answer: Mexican migrants followed the railroads to the Midwest, forging corridors for friends and families to follow. Employment structured these paths to the Midwest and within it. Agencies and employers placed Mexican migrants in temporary and low-paying jobs, often requiring them to live near their place of employment and on the terms of their employer. Mexican mobility and the efforts of labor contractors expanded employment and settlement around railroads in Omaha, St. Paul, Chicago, and small towns and farms in the hinterland of major Midwest and Great Plains cities. Ethnic Mexicans, who employers typically saw as temporary labor, took advantage of seasonal work. They moved between sites of employment, often between urban and rural spaces. Railroad camps, agricultural fields, and meatpacking factories became nodes of a regional Mexican community.

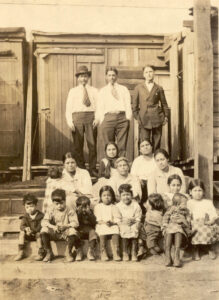

But Mexican migrants were not solely laborers. They were church-goers, ball players, entrepreneurs, patriots, exiles, community organizers, and more. And while this is certainly a story of mobility and movement, it is not one that lacked permanence.

Mexican migrants quickly established permanence in the region, often through religious activities. Mexican migrants founded churches or recurring services in the basements, storefronts, and abandoned churches of cities and rural towns. They did this despite ambivalent leadership of the U.S. Catholic Church and in the face of racism from Anglo parishioners.

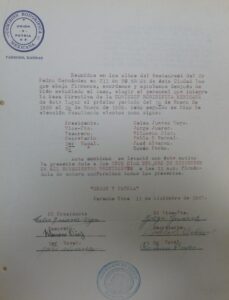

At the same time, Mexican consuls (representatives of the Mexican state) created Comisiones Honoríficas Mexicanas and Las Brigadas de la Cruz Azul to ensure clear connections between Mexican communities and the regional consulate. Then, local Mexican residents often filled the leadership of these arms of the Mexican state.

A Comisión Honorífica served a range of purposes that included social services, cultural activities, and employment protection. Brigadas de la Cruz Azul were women’s auxiliary organizations, though there is limited documentary evidence of only two Cruzes Azules in the Lower Midwest. Overall, Mexican consuls and migrants worked together to create these patriotic societies throughout the Lower Midwest and built an institutional web that connected dispersed Mexican communities to a central consulate, those in Kanas City and St. Louis, Missouri, and then to the Mexican state. As a result, Comisiones Honoríficas and their auxiliary Cruzes Azules simultaneously functioned as extensions of the Mexican state and as sites of negotiation for Mexican migrants to shape a national Mexican identity in the Lower Midwest. Taken all together, we see the building blocks of a regional community: urban and rural hubs; spaces to practice religion and gather, and an organizational web to promote Mexican solidarity and patriotism.

The first instance of “Mapping the Mexican Midwest” provides a partial snapshot of Mexican migrant communities during the interwar years. Visitors can recognize the diversity of Mexican residence in the Lower Midwest, whether occupying multiple neighborhoodss in a larger metropolitan area, relegation to the other side of the tracks in smaller cities, or inhabiting rural towns. By representing Mexican institutions, “Mapping the Mexican Midwest” illustrates that these were not temporary outposts. Mexican migrants established churches and organizations to create a sense of belonging on their terms. While some may frame the region as a white and rural heartland, the visualizations on this site defiantly say otherwise. “Mapping the Mexican Midwest” illustrates how Mexican migrants were part of the economic and social fabric of the region. And now, one can recognize what early twentieth century Mexicans saw: a region filled with their compatriots, churches, and comisiones.